Live from Liverpool: disguise debuts digital spikemark to speed Eurovision Song Contest stage workflow

TV viewers may not have seen them live but Eurovision’s backstage team were the real heroes of the song contest that saw Sweden’s Loreen (pictured above) crowned winner (again) watched in the Grand Final by a record viewing audience. Technicians and stage crew were in charge of 23,700 light sources, 482 costumes, 150 microphones, 100 wigs, 3,000 makeup brushes – and scene changes between acts of just 50 seconds enabled by a disguise custom-designed digital spikemark feature which debuted at the Song Contest

Split-second timing and precision positioning were the key to the fluid and swift change of instrumentation, props for multiple artists in each of 26 different country performances and plus interval acts in the Grand Final. In the week prior to the final, there were another two live broadcasts of the semi-finals and a further three dress rehearsals before a capacity 14000 audience at the M&S Bank Arena, Liverpool.

While Eurovision has yet to release official figures it has tweeted that the final for 2023 was the most watched ever. It’s probable that the 2023 edition will smash previous records which estimates that 160 million people worldwide tune in for some part of the three live broadcasts and that 80-90 million watched the final in 2022.

disguise spent three months developing a digital spikemark solution for the event that illuminated the precise marking for every change of set, instruments and artist on the LED stage floor.

“We used to mark the floor up with tape, so it got pretty messy. Now it’s literally just an operator with an iPad pushing a button. The artist even gets a little ‘T’ mark on stage to show them where to stand, and then we know the spotlight will hit them exactly.”

“With dozens of acts with multiple artists to be precisely positioned on stage, the floor would not only be a mess of tape, the potential for mistakes huge, and the fluidity of production would be challenged,” explains Peter Kirkup, Solutions Director, disguise. “Each act in Eurovision has big ambitious set pieces. Almost every single artist has some sort of set piece on the stage and yet still need to hit these incredibly tight turnaround times taking kit off and setting up the next performance.”

He continues, “In order to do that they have to hit very precise marks because sometimes they’ve got a camera shot that’s lined up to coincide with a lighting effect or some pyrotechnics. The performers need to stand on specific mark points.

“If you were to do that for a traditional show, you would use tape on the floor. But at the level of production demanded of Eurovision and because of its scale we wrote software that had to be non-destructive and need minimal interference from the main production crew.”

Kirkup explains that there have been solutions for this in previous Eurovision using external systems. “What we’ve done is basically moved all of that capability into the disguise services so that they can actually drive it as part of the show and link it into the rest of the show in a much more integral way. Previously we’ve never had this natively in the server.”

How it’s done

All the graphical rendering happens from within the disguise server controlled via iPad. The iPad displays the location of all stage cues per artist with the ability to manipulate, scale, zoom and control them on-the-fly as creative and production needs dictate.

The graphical annotations, which were rendered within disguise hardware and controlled wirelessly via an iPad, were created in the venue by the stage management team based on plans submitted by the delegations. The software was also used by individual artist teams pre-show to stage manage performance. In all, 1250 stage marks were used throughout the show with the help of the digital annotation feature.

“Immediately stage crew doing the scene change can see, for example, a big yellow box illuminated on the LED floor and they’re carrying something that’s the same size as the big yellow box and they put it down in the big yellow box. It makes transferring the items onto the stage really, really, really fast because they don’t have to search for a tiny little tape mark on the stage. It’s just really obvious as they walk 20 metres across the stage, they know where they’re going.”

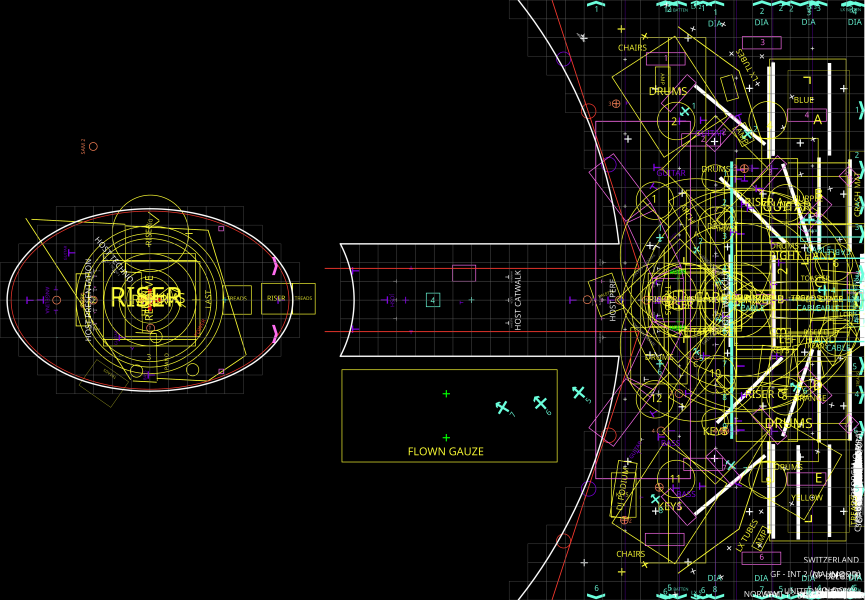

Image showing all of the digital spikemarks for Eurovision combined into a single file.

A team of five programmers, one stage projectionist and two system engineers were responsible for delivering the entire experience, all led by Head of Video, Chris Saunders at Ogle Hog.

“One of the early considerations and really important parts of this was that Eurovision didn’t want this to be something that the operators of the video of the show had to care about. Their job is making all the video work for the show, working with the creative companies. When you have something on the scale and ambition of Eurovision the workflow in terms of stage and performance needs constantly updating. You’ll get halfway through a rehearsal and somebody will decide that actually a piece of scenery needs to move a little bit to fit better with the storytelling of the song.

“If they were to work in a traditional workflow, all of that work would have been put back onto the disguise operators who are managing and editing the video for the event. Making all these scene changes in a conventional manner would not be acceptable because it would have been too disruptive to the main video part of their job.

“Instead, stage management can load up different marks on the stage display in a drag and drop way. They can scale them, move them around. Zoom in, zoom out, work on it just like working in Photoshop or After Effects all on iPad. All of this abstracted from what the video team are doing but it’s all running through the same system.”

Eurovision 2023 stage designer, Julio Himede said, “We used to mark the floor up with tape, so it got pretty messy. Now it’s literally just an operator with an iPad pushing a button. The artist even gets a little ‘T’ mark on stage to show them where to stand, and then we know the spotlight will hit them exactly.”

“The speed is the hardest part, because everybody’s requests were pretty far out there but we’re here to make their dreams come true,” added event Lighting Director, Tim Routledge.

This wasn’t the only piece of disguise technology involved in the show. The stage featured LED screens (supplied by Creative Technology) on the wall, floor, sides and ceiling, each capable of mapping different animations and video and all managed, controlled, synced and played back through six disguise vx 4 (director) and four gx 3 (editor) media servers (all supplied by QED Productions) with storage expansions to increase the drive sizes to handle the volume of content.

“The complexity of catering for more than 37 different acts and several interval acts all with bespoke video content arranged in a multitude of configurations, means the ESC is one of the biggest live events disguise is used for and among the most technically demanding. Each of the artists makes extensive use of the editing workflow within our workstations to design, layer and process their video performance.”

The visuals for the entire show are driven by timecode which is synced within the disguise servers with other production elements.

Kirkup reveals, “There is an extraordinary amount of coordination that goes into Eurovision because the time on the stage per performance is absolutely minimal compared to the amount of time you need to prep it. Imagine something like a mega spreadsheet where everything about Eurovision is stored which is slightly scary because each country will be turning over new versions of the content as artists finesse their performance. So making sure that the servers are up to date with the version that’s been delivered is one challenge. It’s a huge logistical challenge, getting it all pulled together.”

disguise is yet to decide whether the new annotation feature will be made publicly available though Kirkup says there’s a possibility they might release it as an Open Source Project. It could also be adapted for virtual production scenarios.

“The speed is the hardest part, because everybody’s requests were pretty far out there but we’re here to make their dreams come true.”

“The first application is Eurovision but everyone’s kind of gone into this knowing that this is quite a useful thing that could be applied to other markets as well. In virtual production, the common request is for light cards for lighting a chunk of the LED in a flat colour, just to use it as a light source for the scene outside of what the camera would see. You can do this today in disguise, but it’s all work for one operator, whereas actually in this workflow you want to enable a separate person on the lighting team to operate it because they are the ones needing to constantly adjust for reflections and scene illumination.

“It’s not just about plugging in some features and delivering it. There’s really is a need for that holistic understanding of how a show comes together.”

- Media servers supplier: QED Productions

- LED supplier: Faber and Creative Technology

- Projection supplier: QED Productions

- Set Designer: Julio Himede, created by Yellow Studio

- Head of video: Chris Saunders

- Lead disguise Programmer: Luke Collins

- disguise Programmers: Andy Coates, Sam Lisher, Jack Nicklin-Jewell

- Media Wrangler: Ed Joynson

- Stage Projectionist: Alex Pegington

- Systems Engineers: Harry Ricardo, Dan Hall

- disguise Product Engineering team on site: Andy Briggs, Emily Malone, Maximilien Spielbichler

The Eurovision Song Contest took place in Liverpool from Tuesday 9 May to Saturday 13 May, 2023