All in the detail: Volumetric video set to hit touchscreens by end of 2022 says Unity’s Peter Moore

Unity has created a proof of concept with UFC to bring a new level of detail to volumetric video capture

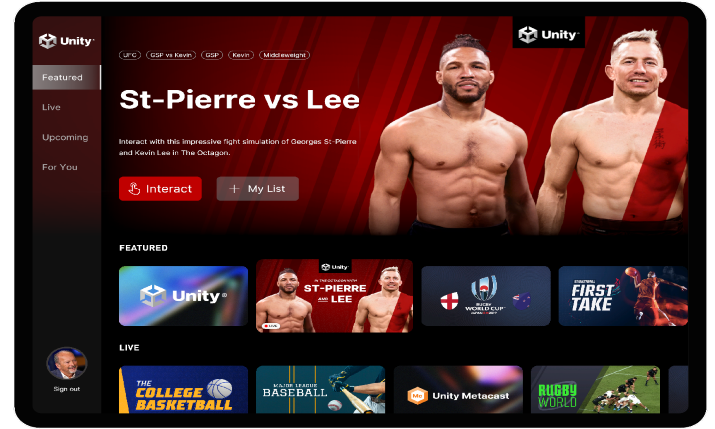

Volumetric video of live sports is set to be hitting viewers’ screens far sooner than they might expect, according to Unity. The company, which is the creator of real-time 3D content development platform Unity, and Unity Metacast, a platform announced in October 2021 designed specifically for use in sports broadcasting, is working with Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) to bring a volumetric video offering to sports fans by the end of the year.

Unity, alongside Cisco and its subsidiary Qwilt, recently joined together to demonstrate how Unity’s Metacast volumetric 3D technology can be transferred onto consumer devices via streaming with low latency.

With Quilt working on the compression algorithms for the overall system, Cisco providing the network, and Unity crunching the data to create the volumetric video, the three demonstrated the system at Mobile World Congress in Barcelona this year with a proof of concept developed with UFC.

“The idea is we capture a full fight card and then probably look internally at what we’ve got and tweak it. But I think we’ll be ready for primetime TV by the end of this calendar year”

Unity SVP and GM of sports and live entertainment, Peter Moore, spoke to SVG Europe about how the company’s technology is pushing volumetric video forward, and what is coming next for viewers. Moore was CEO at Liverpool Football Club for three years ending in 2020, and prior to that, CEO and EVP and Electronic Arts and prior to that EA Sports, and before that a pedigree that includes Microsoft and Sega.

He comments: “What we have looked at it is, how do you utilise data to be able to bring the game to life in real time? As sports fans now we want to know how fast, how hard, how long, records being broken, how many passes made, all of this stuff that, as a lad growing up, you never cared about because it wasn’t available.

“The idea of volumetric is crazy,” adds Moore. “For me as a young guy growing up watching the BBC in black and white and never seeing football or sports at all, except the FA Cup Final, and then having the ability to go to colour [broadcasts], opened up my world in a way that I never imagined in the seventies.

“I think now, going from 2D to 3D [with volumetric video], I think about my three and a half years at Liverpool [Football Club]; Liverpool built its success – and still builds its success – on data capture. Having shown my former colleagues this [technology] the last time I was over in Liverpool, they cannot wait.”

UFC proof of concept

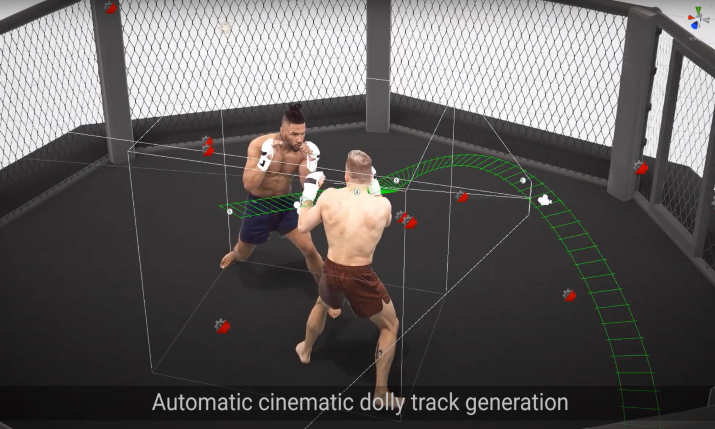

Unity developed its proof of concept using its Metacast technology working in collaboration with UFC. In Los Angeles last year Unity spent a weekend capturing two fighters in action on a sound stage. The result shows the ability to analyse the action in minute detail – the grappling, the punching, the kicking – with outstanding detail rendered in the fighters themselves, from tattoos to facial expressions as punches and kicks land.

“It takes understanding what the consumer wants, it takes the trial and error of, is it the right experience? Is it the right price? Is it just tech for tech’s sake, which is something that I’ve come across many times in the last 25 years of working in tech and sports, or is it something that really enhances engagement and the viewer’s experience?”

Unity’s Metacast is a comprehensive technology stack that empowers content creators to build volumetric experiences. Once content is captured and translated into volumetric data, Metacast provides the tools and technologies that allows the data to be ingested into the Unity editor (encoded, compressed and prepped), rendered, and streamed agnostic of network or device.

On why UFC, Moore says, “it’s just two human beings that you have to capture volumetrically, [in a] controlled environment; no weather to worry about, and an octagon in which you can place cameras”.

He goes on: “If you look at the facial expressions – and I’ve been [working] in video games with Sega, EA, and Xbox for 20 years – we could never capture facial expressions because you have what’s called this ‘uncanny valley’; the face cannot react to the action. What we’re doing here [with Metacast] is capturing the action, so the faces, the grimacing when a kick lands or a punch lands, and I can go back and look at what just happened, and hold, any point in time. The other thing is the octagon is imposed so dynamic advertising can be dropped in.”

In LA last year Unity spent a weekend capturing two UFC fighters in action on a sound stage. The result shows the ability to analyse the action in minute detail

Astounding levels of detail

Looking at the UFC video, Moore adds: “What you’re looking at here is data that’s being reconstituted in the Unity engine. We can go all the way, if you will, to the tap out; we can get down the ground, we can freeze it, look at the position of where [a fighter is] in a defensive position. We think this the level of detail that fans, particularly of UFC, want. So, we’re about six months away from doing this in real time. We’re building an octagon in Vancouver now.”

Unity is building an Octagon of its own so it has full use of the space to create a solid camera plan, then it will transfer that plan to the UFC Apex octagon in Las Vegas. Says Moore: “The idea then is we capture a full fight card and then probably look internally at what we’ve got and tweak it. But I think we’ll be ready for primetime TV by the end of this calendar year.”

That initial offering will be something along the lines of highlights packages pushed out over a stream to end users’ smartphones or onto other touchscreen devices.

In another 12 to 24 months, “you’ll be watching a fight or you’ll be watching a match or watching an NFL game or an NBA game, or even a cricket match, and you will be watching it normally on television, something will happen and you’ll go to your smartphone or your tablet and you’ve either subscribed, or there’s a package that the broadcasters’ put in, and you can go either to an app or a web browser to look at that in real time 3D,” says Moore. “That’s what I think the behaviour will be.”

He continues: “There’s lots of work in between now and that happening, but I’ve been around for a long time; I remember in the late nineties we were trying to figure out how to do video games over the internet, and it felt impossible at that time but somehow we got it done, and here we are today.”

Volumetric video on pay per view would work well for sports like UFC, which could offer viewers the ability to access a volumetric stream of the event for an additional fee, say Moore.

However, he adds: “But it takes time, it takes understanding what the consumer wants, it takes the trial and error of, is it the right experience? Is it the right price? Is it just tech for tech’s sake, which is something that I’ve come across many times in the last 25 years of working in tech and sports, or is it something that really enhances engagement and the viewer’s experience?”

Metacast enables a suite of products, from consumer to B2B. These include interactive streamed 3D mobile applications like the UFC app, to more feature-rich apps for broadcast hosts doing post-game analysis presentations. The technology will also support the rendering of 2D videos for cinematic replay type in-stadium jumbotron and broadcast video ‘impossible camera’ replay applications.

Additionally, says Moore, it will have uses for other members of sports teams as well as for viewers at home, “particularly in the world of medical rehabilitation, injuries, how was the injury caused? How is the player rehabilitating? Can we get him back on the pitch?” Moore says. “We think this is the next frontier of the way we’ll experience sports, and the way we’ll analyse sports.

High bandwidth and low latency

Delivering volumetric content requires very high bandwidth and low latency as it needs to handle anywhere from tens, to hundreds of megabits per second in sustained bitrate. To do this at scale requires purpose-built, data delivery, and data reduction capabilities. As a result, Unity is partnering with communications service provider (CSP) networks and cloud delivery networks (CDN) to get the data as close to viewers as possible. This ensures the most scalable bandwidth and the lowest latency available.

On the issue of distribution of this huge volume of volumetric video to end users, 5G is set to be the answer, Moore says. He states that mobile network operators are interested in volumetric video for sports events as it will entice viewers to subscribe to the necessary delivery network.

Moore says: “At Unity, we capture [content] via our camera partner, who delivers captured data to us, then we render, edit, and author it, we push it down the pipe to a company like Cisco, who then has to deal with the CDNs and then ultimately [the mobile networks].

“So here [in the US] we are [working with] Verizon in particular, because they’ve got a real focus on sports broadcasting; they’ve done a massive deal with the NFL, a 10 year deal with exactly this view of what content they want, [and they’re] not shy about saying, ‘we want people to subscribe to 5G’.

“Ultimately, three or four years from now, we’re going to be talking about 6G; [but] you always need the killer app to make people do that. And that killer app, they believe, in sports, will be volumetric. Right now [for volumetric video] it’s probably about two gigabytes a second pushing through, which 5G can handle. We’ll work on compression algorithms to bring that down… The good news is the pipes just get bigger and bigger.”

On the issue of distribution of this huge volume of volumetric video to end users, 5G is set to be the answer

Camera progression

Metacast is built to be as volumetric-format agnostic as possible. It currently supports polygonal and point-cloud solutions from capture partners such as Canon, 8i, Microsoft and mixed reality capture partners such as Metastage and Dimension, TetaVi and others.

On the challenges in positioning cameras for this kind of capture, the company said that in order to produce a good volumetric reconstruction, cameras must be placed such that they maximise coverage of the subject (ie, can see the subject without obstruction from all angles,) with a good amount of overlap between cameras.

The subjects must also be able to be separated from the background. Furthermore, the cameras must not interfere with the subjects and the physical set up that they perform in.

While all of these requirements are easy to meet in a studio set up, it is much trickier to do for real sports, Unity added. For instance, in the case of UFC, the cameras must not interfere with the referee and athletes.

Every capture provider does it a little differently depending on the quality and physical requirements of the application. For example, some providers use a symmetrical spherical camera configuration set up, while others place cameras strategically with different field of views to capture the entire field of action.

For the UFC demo, Unity used over one hundred cameras. It said that while it is early days for the volumetric medium, with advances in camera technology, 3D reconstruction methods, and machine learning, the company expects to see the required number of cameras drop significantly over time; within a few years, the required number of cameras will be half of what is currently required, perhaps even less. It added that there are techniques that work with only one camera, which while not yet at an acceptable level of quality, may rapidly change.

Boxing to football capture

On which sports we might be able to watch with volumetric video, Moore says the net is being thrown wide. He explains: “We think about crawl, walk, run; I’ve met with the NBA. One of the great things about [being the former] president of EA Sports is I wrote rather large cheques to all of these leagues, and they all remember the size of the checks that I wrote for video licenses. So, I’m able to walk into any of the offices in New York, which I’ve done, and show them the tech.

“I think the next environment [we will move to] are closed arenas; you need a closed environment [at this point to enable the camera set up to work]. As the tech evolves, eventually we’ll get to stadiums. But I think of UFC, boxing, maybe WWE as the first step, then think of arenas, basketball, hockey; indoors, close to the action, closed environment, consistent lighting, tight number of players playing in a small space, and eventually we’ve got to figure out soccer, and you saw the Canon [2019 Rugby World Cup trial]; albeit the resolution wasn’t great, but Canon certainly were able to do rugby.

“I think at first, it may well be in the big stadiums, you’re just behind one goal and you start capturing the action [there] and the focus is on the penalty area, which is 90% of what people will want to see in there. Then eventually you’ll figure out stadium-wide and get that experience right,” concludes Moore.

“It’ll be a few years from now, and I’ll be in my rocking chair by then, but we’ll figure it all out.”