Making Paralympic history: Giles Long on bringing para sports to the masses

Lexi being used in the stadium at the London 2017 IPC World Athletics Championships

Channel 4’s coverage of the 2012 London Paralympics was for many the first time para sports were explained in a way that meant the viewer could really engage with the athletes and their achievements.

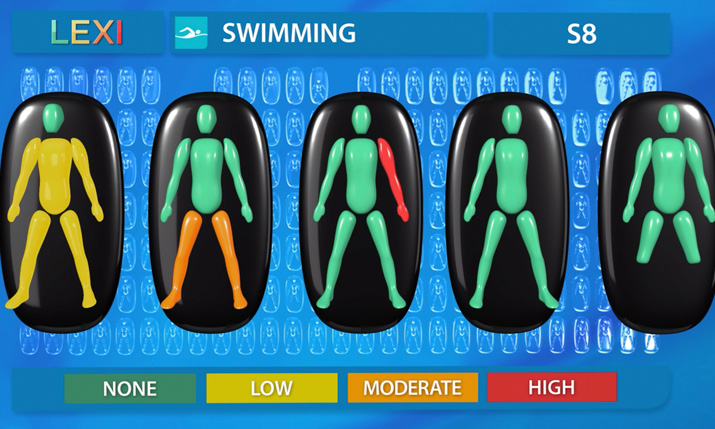

The reason for this was Lexi, a groundbreaking info-graphics system that gave viewers a series of colour-coded human-shaped icons on the screen that showed the classifications of the athletes in their events prior to each race, taking away the confusion around who was racing and why, and opening up the enjoyment of the competition instead.

The man behind Lexi is Giles Long MBE, a Paralympic gold medallist swimmer who came up with the idea for a simple way to illustrate para-sport classification.

Fair in the eyes of the viewer

The original concept for Lexi occurred to Long when he was competing in the Sydney Paralympics in 2000. He explains how: “One of my teammates, a guy called Sascha Kindred, was racing in the 100 Breaststroke against a Chinese swimmer called Baoren Gong. The race was absolutely head to head, neck and neck coming into the last five metres.”

Long explains that Gong has no arms while Kindred is affected down one side of his body with cerebral palsy. The issue came about simply in the way the two athletes finished the race due to their disabilities. Long continues: “The way the BBC edited the race at the time was they only showed the final seven metres of it because everything was happening in highlights, because it was in Australia. It comes down to the final two feet [of the race] and of course, Sascha whips his hands out to touch the wall, whereas the Chinese guy has to touch the wall with his head, and Sascha wins the race.

Giles Long at the Homecoming Parade in London 2004 post the Athens Paralympics

“When we got home, everyone just kept telling me, ‘wow, wasn’t that Chinese guy amazing?’, and really what they were saying was they thought the race wasn’t fair. That’s what it boiled down to. I thought, ‘well, if you think that race isn’t fair, do you think that about my race? I don’t want you looking at my gold medal thinking, ‘did Giles win this because of the way the rules are written?’.’ I thought this sport isn’t going to grow if people don’t understand it.”

Understanding a sport is the only way to fully engage with it, and to appreciate the efforts of the athletes, Long says: “People engage with football because every single eyeball watching the screen understands every single second of what is going on. If you understand every single second it means you feel completely justified in forming your own opinion.

“Being able to express an opinion and feeling that it’s a credible opinion is a whole new level of engagement rather than just watching someone and effectively someone saying, ‘I know it doesn’t look fair, but it is, just accept it’. All you’re going to get from that is people will be inspired, but they’ll only ever be watching on a superficial level. I thought, ‘we’ve got to explain this to people; we’ve got to explain why these categories are fair’. My dad’s a graphic designer and he always used to say to me when I was growing up, ‘if you’ve got a lot to say in a short space of time, use a picture’.”

Birth of Lexi

This is the point where he began to come up with the idea for Lexi: “I just thought it was obvious; we can have these little human characters on screen, colour them in traffic light colours to show which parts of the body work and which parts don’t, and we could just explain to people, this is why a seemingly different looking group of people are put together, and explain it in a sporting context, and we could do that in seconds and the viewers would understand what the class is before the race is run.”

He says there had always been a lot of resistance to talking about disability in para sport at that time because people did not want to point out the differences in people but instead to just talk about the sport. He adds that, “the ironic thing in paralympic sport is if you don’t talk about the disability up front, as a commentator you spend all of your time having to back reference the disability because otherwise your comments don’t make sense as you haven’t established a framework for what you’re talking about”.

A Lexi full frame still from the 2018 Commonwealth Games

He suggested his idea to the BBC in 2004, “and didn’t get anywhere,” then again in 2008, “and didn’t get anywhere”. Then when he was trying to become a presenter in 2012 for Channel 4, in a meeting with the executive producer things changed.

He explained: “The exec producer said, ‘by the way, we’ve committed to explaining classification and that’s one of the reasons why we’ve won the bid to screen the Games, have you got any ideas?’ and I just said, ‘well yeah, funnily enough I do’. I drew it for him with a biro on a notepad and said ‘it works like this, these characters come up and this is what the voice says’, and because I’d been thinking about it for so long I knew exactly how it worked.

“We still had to overcome every single hurdle; there was a still a large contingent of people within the para sport community who still had that whole thing of ‘don’t talk about disability’ and that understandably caused a lot of nervousness at Channel 4,” Longo continues. “In the end what it came down to was Channel 4 saying they had said they were going to crack this [classification explanation] and this is going to be the way we’re going to do it.”

Channel 4 commissioned Long to develop his idea and create Lexi as his own company. Long went through the design process, experimenting with 20 different re-draws, different shapes, and different colour schemes. In the end he came up with a human shape that is standing square to the screen while still looking dynamic and sporty. It is unisex so can be used to front a female or a male race, and the colours scheme uses the universally understood traffic lights scheme plus orange to increase the flexibility in classification.

Making para sports transparent

Lexi is successful because it makes everything about a para sport event transparent for the viewer. Long states: “If you just clear the decks from the start and just say, ‘right, this next race is people with this, this, this and this, and the reason they’re grouped together in this sport is for this reason’, then people are like, ‘alright, cool, on we go, let’s hope Britain wins’.”

It went on screen in the UK with Channel 4 for the 2012 Paralympic Games, as well as being sub-licensed to ABC in Australia. Lexi then was used in Sochi in the UK and in Russia (on RBC), while Rio marked a major step forward as it went on screen in the UK, US, Canada, Japan and Australia. The same countries used Lexi for Pyeongchang as well as the addition of Germany.

Long adds: “We’d also had some major success with the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow in 2014, when it went to 76 countries, and then 2018 the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games we went to 137 countries.”

Lexi used as an overlay on top of sports footage as a single icon per athlete at the Pyeongchang 2018 Paralympics

Lexi allows the storytelling process of commentating on sport to work properly, Long states. He says there is a correct way to tell a story when watching a live race on screen, yet prior to Lexi, para sports were commentated on in a back to front fashion that reduced the sporting accomplishments of the race winners.

He says: “There’s a very specific order in which sport has to be broadcast and that is effectively knowledge of the game, the event itself, then the colour bit afterwards, so it’s like works like this: here’s what an S8 [classification for para sports] is, now let’s watch the 100 metre butterfly, it’s been won by Giles Long, congratulations and then let’s hear about why he swims with one arm.

“If you watch football, rugby, tennis, it’s always in that order, and really, until Lexi came along, Paralympics was always in reverse,” he explains. “Before the race, people would be talking about my trips to hospital and cancer and stuff like that, then people wouldn’t understand [the classifications] during the race, and afterwards the first question, instead of ‘how does it feel to have broken the world record?’, would be ‘so you lost arm, tell us about that’, and the third question would be, ‘you broke the world record, how do you feel about that?’ Everything was backwards. By putting that information upfront, it aligns it with the way sport should be broadcast; you’re creating a framework for people to understand achievement.”

Childhood obsession with water

Long began his obsession with the water at a young age, joining his local swimming club in Braintree, Essex, UK, following a suggestion from his mother. He says: “I was just one of those kids who always loved being in the water. When I was seven I was sitting in the car and my mum looked in the rear view mirror and said to me, ‘would you like to join swimming club?’, and I thought that sounded like a great idea, so I did.

“I had loads of friends there and started competing, and I was good. I very quickly had a dream to go into the Olympics as well, and I told my mum and dad, ‘I’m going to go to the Olympics and I’m going to win a gold medal!’. What was really important was they didn’t laugh at me; they were just really supportive and kind of threw the challenge back at me and asked how I was going to do that. As a seven year old I didn’t really know, but I carried on training more and more and competing as I got older and go better and better,” he remembers.

Lexi in use at the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games as an overlay on studio footage

His dreams of going to the Olympics were shattered in the school playground just a few years later, however. “When I was 13 I fell over at school and broke my arm, very high up close to my shoulder. The reason my arm had broken in such an unusual place was because I had a bone tumour [osteosarcoma].”

Chemotherapy, radiotherapy and several operations followed over a two year period for Long. “I had chemotherapy and I had the bone that connects you shoulder to your elbow, which ironically is called the humerus, replaced with an internal metal prosthesis (a metal bone). Part of that operation meant I lost all my shoulder muscles in my right side. So if you’re a swimmer who has dreams of going to the Olympics and you can’t rotate your shoulder any more… it was just an absolutely nightmare; my Achilles heel.”

Although his world had been turned upside down, Long continued to swim. “I carried on swimming even though that Olympic dream had been battered to death, because of all the good mates I had at swimming club. Then my coach started to enter me in competitions, as he said everyone that was at swimming club has to do competitions, so if you want to keep coming you have to keep doing them. I used to get beaten every time because I’d be swimming with one arm and everyone else would be swimming with two.”

Facing up to a new reality

Long was at a competition in East London, very close to where Olympic Park is now, when at the age of 16 he was spotted by a member of the GB Paralympics team who invited him to a training weekend.

He says: “I went along to that training weekend and there were a lot of GB Paralympians there, but I hadn’t come to terms with the fact that I now had a disability. All of a sudden I was there, confronted with it. Times were very, very different then, 20 or 30 years ago. People just saw it as you have a disability and that is who you are; you don’t have other interests and you certainly don’t have hopes, dreams and aspirations, because probably the biggest thing you can aspire to is to get down to the supermarket to buy a tin of beans without an incident. That’s just how people thought about it, and I was no exception to that, and in my mind I rejected it.”

He was at another swimming competition at his home town of Braintree when the head coach of the GB swimming team for the Moscow Olympics approached him. Unbeknown to Long, the coach also did a lot of work to help aspiring Paralympians as well. He asked Long if he had any dreams of going to the Paralympics, as he had watched him swim and was impressed.

However, Long says: “I just kind of went, ‘nah’. He then said, ‘I also hear you’ve been pretty ill, and maybe before you were ill you could do 10,000 things, so now after a bit of bad luck you can only do 9,000 things, and that means you have a choice; you can either concentrate on the 1,000 things you can’t do anymore, or can concentrate on the 9,000 things you can still do’. I’d love to be able to say that it was a real light bulb moment, but in truth it more kind of seeped in over a few weeks and got me thinking, deep down inside I still really loved swimming and maybe this was a path to try and fulfil that dream of 10 years before.”

Start of the Paralympic dream

Lexi icons demonstrating athlete classifications in the water

He started training properly and went to his first Paralympics in Atlanta in 1996, winning gold in the S8 100 metre butterfly. Next was various World and European Championships before the Sydney Paralympics, where he took gold for the S8 100 metre butterfly again, as well as beating the world record time for that race. Then he went onto the Athens Paralympics in 2004 and swam a British record time in the butterfly, and took home the bronze medal. He was awarded the MBE by Queen Elizabeth II in 2005.

Long rounded off his swimming career in 2007 after attending a World Championships in December 2006 where he was, “beaten by a load of 19 years olds,” he laughs. “I just thought, ‘do you know what, I’ve done all I need to do in this sport! OK guys, I get the message, over to you!’”

After retiring from swimming, Long began commentating in venue at swimming events. Leading up to the 2012 Paralympics he presented live coverage of the 2010 IPC World Swimming Championships, the 2011 IPC European Swimming Championships, reports for That Paralympic Show, as well as working for BBC News and Sky News.

He adds: “The real injection of fresh talent in to the paralympic space was when the rights for 2012 went to Channel 4; it was a really important time when, for the first time, the rights to the Paralympics were sold separately to the rights for the Olympics. Prior to 2012, if you bought the rights to the Olympics you automatically got the rights to the Paralympics and that meant it was very difficult for Paralympic talent to actually get a break into [commentating] as you had broadcasters saying, ‘well, we’ll just use the same team that did the Olympics’.

“Where we see the innovation there for a broadcaster is rather than having this tool, what you are effectively doing is turning every presenter and every commentator into an expert on classification.”

“Channel 4 had the rights all of a sudden and they had to build a team [of commentators and presenters] from scratch and they wanted it to be distinctive; they were very clear that they wanted new people and fresh faces. That and the run-up competitions to the 2012 Games was where I cut my teeth a bit in [commentating]. It was full-on turbo for 2012. I found myself not only as the key or co-commentator for the swimming, but the key pundit for classification [of all disabilities] across all sports.

“Because I’d developed Lexi for Channel 4 for 2012, I was probably one of the few people in the world who understood classification across all sports. So I started off as a swimming expert and by days seven, eight, nine [of the Paralympics], presenters started asking me questions like, ‘how does classification work in athletics?, how about archery, how about basketball?’, so the job just grew as the Games wore on really.”

Post London 2012 he has continued to be a presenter and commentator on Channel 4’s coverage of Swimming but also worked for the BBC on their flagship consumer show, Watchdog. He was again part of Channel 4’s presenting team for the Rio 2016 Paralympics and will be again in Tokyo.

Taking Lexi forwards

The future of Lexi is already here, says Giles, who points to how the graphics were used at the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games by host broadcaster, NEP, as how he sees it being used in the future. Lexi was overlaid on the lower third of the screen in the studio on top of presenters, with those presenters providing the voice over explanation of what Lexi is showing, or was shown as an overlay in the same way on top of pre race footage with commentators providing viewers with the explanation, rather than only being used as a full-frame video.

Long explains why this is an important step forward: “Where we see the innovation there for a broadcaster is rather than having this tool, what you are effectively doing is turning every presenter and every commentator into an expert on classification. So you’ve got this continual drip-feed of information for your viewer, just at the point where they might start to be wondering what’s going on, to keep the engagement bouncing along at a high level. We’re always about getting people to understand the classification before the race starts, that’s the crucial thing.”

He adds: “For the Commonwealth Games we worked with the host broadcaster but also very closely with the Host Broadcasting Committee, and Commonwealth Games Federation is very forward looking; it’s the only big sporting event in the world where para sport events are integrated directly into the main sporting programme. That then created quite a nice way of [switching from able-bodied events] to para events.”

Used in this way, Lexi also solves problems of language as well, states Long, who points out that although the graphic is on the host feed as at the Commonwealth Games, broadcasters are able to do their own voiced explanation over the top of the graphics in their own language.

Lexi is in discussion with all the key broadcasters about this use of the graphic for Tokyo 2020.

Long concludes: “Tokyo will be the first games where we have every class for every event and every sport. Some of those sports are ones we haven’t covered before; badminton is going to be in Tokyo for the first time [at a Paralympics]. Off the top of my head, that’s somewhere around 250 different classes across the Paralympics.”