ORF takes skiing close to the edge at the 83rd Kitzbühel Hahnenkamm Races

Over the weekend (16-22 January 2023), winter sports broadcasters returned to the Streif in Austria for the Hahnenkamm Races, reputedly the toughest downhill skiing challenge on earth.

This year, the 83rd time the competition has taken place on the mountain, the FIS Alpine Ski World Cup race could be witnessed worldwide by a television viewing audience of more than 500 million people.

The technically difficult Streif is divided into three dramatic sectors: Start to the Steilhang, Brückenschuss to Oberhausberg, and Hausbergkante to the Finish – in all, it is 3312m long and drops for a vertical of 860m. The course twists and turns furiously, with blind drops and terrifying jumps; one of these, the Mausefalle, has a gradient of 85% and launches the racers 80m through the air.

The broadcast coverage is a mixture between close-up, long shots, wide shots, drone shots that can accelerate alongside the skiers at more than 100 km/h, and in at least one case a barrel shot resembling the view from a looping rollercoaster, courtesy of camera cranes. It all makes for a dramatic race and great sports broadcasting.

“I believe 100% that you need a great picture, but without the right sound, the picture doesn’t work. So we’re putting a lot of effort into audio. “There are microphones everywhere.”

Michael Kögler (pictured above, right), head of directors at ORF Sport, has been covering the race since 1987 and has overseen the host broadcast for eight years.

“There’s a lot of coverage from top to bottom,” he says. “We’re covering this with 50 cameras, including two drone cameras and 12 high-speed slo-mo cameras. There are five cranes in the operation and two pole cams. For Austrian TV, this is our Superbowl; for the importance of the sport, it’s like Wimbledon, Augusta, or Formula 1 in Monte Carlo.”

Kögler views the participating ski racers as the underrated athletes of winter sports. “The icy surface is like concrete and it’s a vertical drop,” he says. “They are going at speeds up to 150 km/hour; they have nothing to protect themselves but a helmet and back protector. If they make a mistake they can crash, and it will really hurt them. So there’s real danger there

– these athletes are heroes.”

An ORF camera operator at the foot of the Streif in 2022

“It’s always difficult with the sport to show the speed as it is two-dimensional on TV, and also, it’s very tricky to show how steep these slopes are,” says Kögler. “Most of the time it’s impossible to show this to the spectators at home, but with the drones and with the cranes we are operating, there’s now a chance to see it. The drones give you enormous insight into how fast the skiers go, and what kind of skills they’ve got to have.”

For example, Kögler says a drone shot used to capture a traverse part of the race, shows “how really traumatic this part is, [how hard it is] to keep yourself on the hill because it’s such a deep hang to the right side. Whenever you lose contact with the skis, there’s a chance that you might lose your whole balance and crash into the net”.

Kögler says he seeks a balance between the action scenes and more emotional shots of the racers preparing for the race, “showing that a human being is behind it, and able to do these things”.

The single lightly clad figure dwarfed by the scale of the mountain and moving at the speed of a racing car, with features completely enclosed in a helmet, throws up challenges to the winter sports broadcaster that those covering tennis or football stars might not encounter.

“Most of the time it’s impossible to show speed to the spectators at home, but with the drones and with the cranes we are operating, there’s now a chance to see it. The drones give you enormous insight into how fast the skiers go.”

Kögler attempts to tackle these dehumanising factors and add an emotional connection by stationing cameras to cover the warm-up area in the ‘Starthaus’ [1,665m above sea level] before the race. “There, you can see their faces,” he explains.

“There’s a lot of talking and jokes going on there. But when they go onto the start gate area, you don’t hear anything; there’s just silence. So I always try to show them going to the start area; you see a close-up of their faces when they start to focus on the race. If you talk to them afterwards, they’ll tell you: “I knew when I was going out there: either I’m going to hospital, or I’ll win this race”.

An additional human perspective is added when they arrive at the finish area. “There’s a big crowd waiting there with 50,000 people cheering for the racers,” adds Kögler. “We have cameras there to focus on the spectators.

There are also a lot of celebrities who come here, like [Arnold] Schwarzenegger, and all the really big football players. So on the one hand we have these VIPS and on the other the normal fans cheering for the athletes; it’s all part of the mix for this race, which makes it so special.”

Michael Kögler, head of directors at ORF Sport, (pictured, left) in the gallery

Almost 100 broadcasters in total were reporting on the Streif in 2023. Host broadcaster ORF screens the competition’s three major races (two downhill and a slalom) live on ORF 1, as well as covering training runs, and also streams content on ORF-TV-thek within Austria. ZDF was broadcasting from Kitzbühel for German viewers on all three race days, while SRG covered them for Swiss audiences.

Also broadcasting live from Kitzbühel was NBC – the race has a long history of being shown in America – while Eurosport 2 and Italy’s Rai were also broadcasting live throughout the weekend. According to Kögler, there were 50 countries covering the last day of the event.

ORF provides the OB for the race, with additional suppliers for the drones and cranes. “This is a big operation, with around 200 people working on it,” says Kögler.

The significant coverage requires a sizeable investment in infrastructure.

“A lot of stuff is already pre-cabled to some spots [on the course]. But there is still tonnes of equipment to be flown up because there are so many things to [cover],” he says. “Since I’ve been in charge for the last nine years, I’ve added about 12 cameras, and I’ve changed more than 50 camera positions from where they used to be; I’ve moved cameras or cranes by up to 30m just to get a better shot.”

This year Kögler decided to change the focus and position of cameras around the Mausefalle, a jump that skiers encounter around eight seconds after the start.

“It’s enormously steep, more than 80% [gradient]. We [originally] had the crane [cover] the middle of the part where they land, but we’ve now moved to behind the point for the take-off so that we can follow him speeding up the ramp,” he explains.

“[The shot] is like being on a rollercoaster, when you get to the highest part and right before you go down. That’s the feeling we’re giving [viewers] with the crane shot. We’ve tried to follow [the skier] from behind and give the audience at home the feeling that they’re jumping with him.”

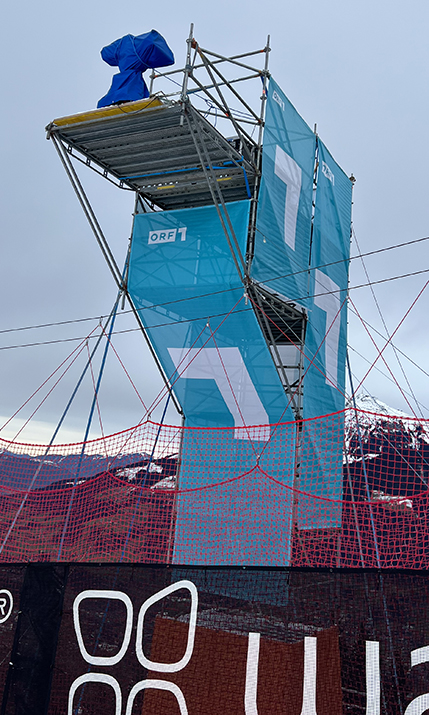

A camera tower on the race course

The production deploys a mixture of cameras with long lenses on towers – as there is a lot of netting around the course, ORF has to build extra-high towers to get clear shots from these positions – and handheld camera operators on the slopes, who are protected by barriers in case a racer crashes into them.

Audio is also a big consideration.

“We’re really focusing on the audio, including putting additional equipment on the gate and [around] the spots where they’re landing,” he says. “There are microphones everywhere. We have a sound engineer and sound designer here who are trying to [convey] this really ‘dangerous’ sound of the ice.

“I believe 100% that you need a great picture, but without the right sound, the picture doesn’t work,” he continues. “So we’re putting a lot of effort into audio, especially in the past two years since we added the sound designer during COVID to bring additional [layers] to it. It’s really a strong sound.”

This focus on audio is set to continue. “In the future, I would like to integrate the [microphone] into the [skiers’] bibs, so I can get audio from each of the athletes when they are racing,” says Kögler

“Some of them are talking and you can hear it on the microphones we already have, but if you could have a microphone integrated into each bib that would be fantastic because then I can hear every sound from the athlete, such as their breathing, and this would surely bring additional drama to the show.”

“[The shot] is like being on a rollercoaster. That’s the feeling we’re giving [viewers] with the crane shot. We’ve tried to follow [the skier] from behind and give the audience at home the feeling that they’re jumping with him.”

“I want to always bring the audience as close as possible to the action, as close as possible to all the athletes,” says Kögler. “This is why we started to use the drone, because it offers viewers at home a little bit more of what the race looks like, how the athlete is encountering the challenges. It’s also something which [might appeal] to a younger audience – it looks more like a video game. So as well as additional insights for the audience, it might bring in a new audience to this cool sport.”

The drone operators are highly accomplished, as are the camera operators, who need to be skilled skiers themselves.

“Going down the slopes to reach your position is not easy because it’s really dangerous,” Kögler says. “It’s also dangerous for the guys who are working on the icy platform. [Camera operators] have to stand there in the cold for three hours, so it’s tough hard work. But everybody on this production is passionate about it, the whole team is working together, and they are happy to come here. If you’re an Austrian into ski races, you’re waiting for this for a whole year; everyone wants to be involved.”

The 83rd Hahnenkamm Races took place in Kitzbühel, Austria from 16 to 22 January 2023