Three is the magic number: How FilmNova and the PTO covered The Collins Cup, triathlon’s biggest challenge

The Collins Cup, the main event in the Professional Triathletes Organisation (PTO) calendar, took place in Slovakia at the end of August and was shown live in over 100 countries. In this article, we take a look back at the massive effort, multiple challenges and military involvement behind broadcasting coverage of the event.

It’s great when a plan comes together. It’s even better when it works out far better than expected.

“When we started, we felt that we might be streaming live, but we weren’t sure about what the appetite would be for linear broadcast,” says Martin Turner, executive producer of The Collins Cup coverage.

“In the end, we broadcast live in over 100 territories for the whole event. It was quite extraordinary. The main coverage was 55 territories in Eurosport as well as Japan, America, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, all the main countries that have an interest in triathlon. We’re waiting for our full analysis of ratings, but the feedback from all the broadcasters has been fantastic.”

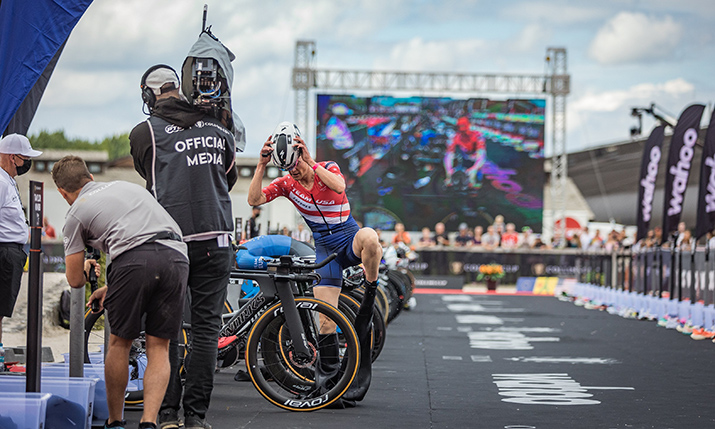

Šamorín in Slovakia was the field of play for the Collins Cup, with 36 pro triathletes making up three teams of six men and six women, representing the USA, Europe and Internationals. Individual matches saw three athletes slug it out from each team, offering fans twelve separate races in all.

“You’ve potentially got [to cover] 36 locations at any one time, and you’ve got to get to them all fairly seamlessly,” says Turner.

“When you cover golf, you’ve got stories happening on each of the 18 holes, you’ve got static cameras and moveable cameras but you’ve essentially got every hole covered and each separate story comes to you. Whereas at our event, we had to go to each match, we had to follow each athlete. The RF challenge was immense.”

“We had to get special dispensation from the Slovakian military government to allow us to use military frequencies.”

Of course, this is television, not CCTV, so there’s a story to tell too. “From a narrative perspective, it’s essentially one story: the USA versus Europe versus the Internationals, but it’s cut up into 12 different events,” says Turner.

“It’s also complicated by the fact that you don’t only get points for finishing, you get points for finishing by winning a match by a certain amount or losing a match by a certain amount. You have to follow the story and know wherever you are at any one time, who’s leading, what’s going to change and explain the jeopardy. You’re also telling individual stories, and keeping people up to date with the flow of the seven-hour event.”

A state-of-the-art timing system was used for the first time, while specialist cameras enhanced the coverage and helped to explain who the athletes were.

“It was a massive task we gave ourselves and we took on a lot of new challenges,” says Turner. “We tried a lot of new things and by and large, most of them worked.”

Managing frequencies

The production company was FilmNova, with director Matthew Coliandris and programme producer Jim Bentley leading the world feed coverage.

“Our background is in complicated OB, but when we saw the footprint we were faced with in Šamorín, that was a challenge above anything we’ve done before,” says FilmNova managing director Phil Sibson.

“When we took it to NEP, they said it was the most amount of RF frequencies they’ve ever had to request for a single job. We had to get special dispensation from the Slovakian military government to allow us to use military frequencies.”

NEP The Netherlands deployed a 100-man crew, 12 motorbikes with each match group and a Quadbike to capture race finishes. A Wirecam, suspended by 20m towers with 16 tonnes of ballast acting as counterweights, provided coverage of transitions.

There were 30 cameras in total, including Steadicams, mobile and handheld RF cameras, Jibs, a Helitele and several specialist cameras, all linked by a fixed-wing relay plane. The graphics were supplied by AE Live.

“It was a logistical headache for NEP in that when they couldn’t cover a group by RF that they had to have a strong enough 4G signal to bring back pictures.”

Although the production had a fixed-wing plane flying at altitude for RF signals, Sibson says this usually only covers around 10km, while the footprint for the whole course was about 30km.

“The format of the competition was such that we knew that we would have athletes spread out over the extremities of the course, so we couldn’t just position the plane over one part,” says Sibson. “So it was backed up by 4G as well.”

Each of the motorbikes was equipped with both Vislink RF and Mobile Viewpoint WMT 4G encoders. “From the off, we realised the only way that we could keep track of everyone on the course was by having a moto with every group,” he adds. “We needed those motos to stick with each group and move around with them.

“It was a logistical headache for NEP in that when they couldn’t cover a group by RF that they had to have a strong enough 4G signal to bring back pictures. There were also black spots on the course where there was no 4G coverage. NEP did an amazing job of making sure that when we didn’t have 4G the RF was there and when we didn’t have RF we had 4G.

“So the fact that the signals were so solid throughout the whole seven hours is just staggering and a real achievement.”

Weathering the storm

“The main scanners, the edit and the highlight scanner and the replay scanner and the directing gallery were all on-site in expandable NEP trucks. The graphics operation for AE Live was in a fly case but that was on-site,” says Turner.

The audio was challenging, as was the weather. “When you’re doing something for the first time, not everything is always going to work,” says Sibson.

“We were hoping to get all the communication between the athletes and their team captains who are based in transition, on air. It was quite a feat getting the equipment onto the athlete’s bikes sites. It worked in testing, but we suffered quite a lot of adverse weather conditions.

“For example, the equipment on Jan Frodeno’s bike got waterlogged while we were waiting for him to come out from the swim.”

“We started with absolutely perfect weather then we had a situation where we were dealing with monsoon conditions,” adds Turner. “The event might have been cancelled or certainly postponed, but we were already halfway through. We had three women’s matches out but they had to delay the start of the men’s races by 10 minutes because the weather was so inclement.

“You can’t always predict that your story is going to play out at the time when you want to use the particular equipment,” continues Turner. “We had it working and we were talking to the athletes, and the athlete was talking to the captain. But editorially we weren’t able to get to it at the right time; by the time we got to the story, we were into a dark zone. Just one of the many challenges of something that takes place over such a wide footprint.”

Bring in the specialists

As SVG Europe previewed back in March, the Collins Cup saw innovative use of specialist cameras and technology to enhance the coverage, including the Bolt High-Speed Camera Robot from Mark Roberts Motion Control on a 12m track.

“I’m sure it’s the first time the Bolt has been used in a live sports environment,” says Sibson. “We used it with a Phantom Flex camera, which had a frame rate of 500fps. The idea of that was that we could use it in preproduction to produce stylised idents of the athletes, but then in the actual race, we had it positioned between swim exits and T2 [bike to run] transition.

“We had a tent [the Bolt Zone] in the field of play with Bolt on the track down the middle. On one side the athletes were coming out of the water, and on the other side, we were able to get them when they were going back out on the run. It provided some really dynamic shots.”

“Thankfully the PTO’s ambition was matched by realistic budgets. That is all too rare, but they backed us completely.”

“We also used the AntelopeAIR [Extreme Slow Motion + Live Camera System from LMC], which gave us RF high motion pictures,” says Turner. “[Normally] hi mo and super slo mo are fixed cameras and camera positions, you only get the value of them in the context in which they’re placed, but with the AntelopeAIR, operated by the legendary Steve Rouse, we were able to get high motion pictures of athletes, fans, and shots from the start of the swim to transition, all over the site, and the closing moments at the end of each run.

“I’ve done it before in other sports, but to do it over such a large footprint gave us a hell of a lot of value, if a bit of a sore shoulder for Steve Rouse,” he adds.

A HeliTeli was deployed, supplied by NEP with a local crew. “They’re very good at what they do, they’re used to doing UCI cycling and Tour de France,” says Sibson. “It could have been a real headache to try and move that around to where it needed to be but it was pretty seamless.”

Polecam was used for the swimming coverage. “Unlike traditional triathlon where you have a melee of swimmers in at one time, we knew that we would have three athletes in each group, and there were only ever going to be three groups in the water at any one time,” explains Sibson. “It meant that we could manage with two boats, working in tandem, plus our land-based cameras. So we had a Polecam on one boat, and a stabilised lens on another.”

Feed the world

The PTO and FilmNova took on the role of host broadcaster. “We broadcast the whole event and presented world feeds for the use of everyone, but we also looked after Eurosport’s presentation needs because they were easily the largest broadcaster,” says Turner.

“We had two very experienced presenters in Alex Payne and Charlie Webster. We had an extensive commentary team led by Phil Liggett with contributions from the likes of Greg Bennett, Belinda Granger, Vicki Holland: all world champions and Olympians. So, we had a marvellous team behind the camera, on the microphone and in front of the camera.”

“We had satellite path off the site, with a backup in case there was an issue with one of the satellites,” says Sibson. “It went into BT Tower, and from BT tower out to distribution worldwide. BT Tower was also where we were encoding for online [provided through] RTMP streams.

“The feedback we’ve got from fans and professionals alike, and the athletes, is all firmly in the positive camp. I think you can say we’re very happy with what we’ve done.”

“From our point of view, the thing that we’ve been most pleased with is that our philosophy of coverage that we took to Martin and the PTO back in February 2020 – Matthew Caliendro’s camera plan, the need to stick with each group, the dual use of RF and 4G, plus all the fixed cameras that are necessary around transition start and finish – all remained largely unchanged,” continues Sibson. “Thankfully the PTO’s ambition was matched by realistic budgets. That is all too rare, but they backed us completely and Martin’s been a big part of that.”

The broadcasters were also pleased with the result. “They were very, very happy with what they got, which was very gratifying for us,” says Turner.

“They felt it was exactly what we promised, a much higher level production than triathlon has ever seen before. And with a new format as well. When it’s the first time you’ve done something, and you’re selling a dream or a vision, it’s not always easy to deliver. I can say quite easily that we delivered it to a level of production higher than the Olympics in terms of their triathlon coverage.

“The feedback we’ve got from fans and professionals alike, and the athletes, is all firmly in the positive camp. I think you can say we’re very happy with what we’ve done.”

The 2021 Collins Cup took place on Saturday 28 August in Šamorín, Slovakia.